An excerpt from the forthcoming issue of City Health Magazine

Bird flu is spreading in the U.S. While the number of severe human cases remains low, the slow response from the federal government and a recent human death from the virus are raising alarms.

The H5N1 variant, also known as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), was first identified nearly 30 years ago among domestic waterfowl in Southern China. Sporadic human infections have been reported in 23 countries since then. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of December 31, 2024, there have been 954 confirmed cases of H5N1 infection in humans worldwide, with 464 fatalities (49%). (For comparison, the COVID-19 fatality rate in the U.S. in 2020 was 2-3%.)

Today, H5N1 is widespread among wild birds worldwide, and has spread to infect wild terrestrial and marine mammals as well as domestic mammals.

In the U.S., it was first detected among domestic poultry in 2022. In March 2024 it began spreading through U.S. dairy herds, and at latest count has been detected in 972 herds across 16 states.

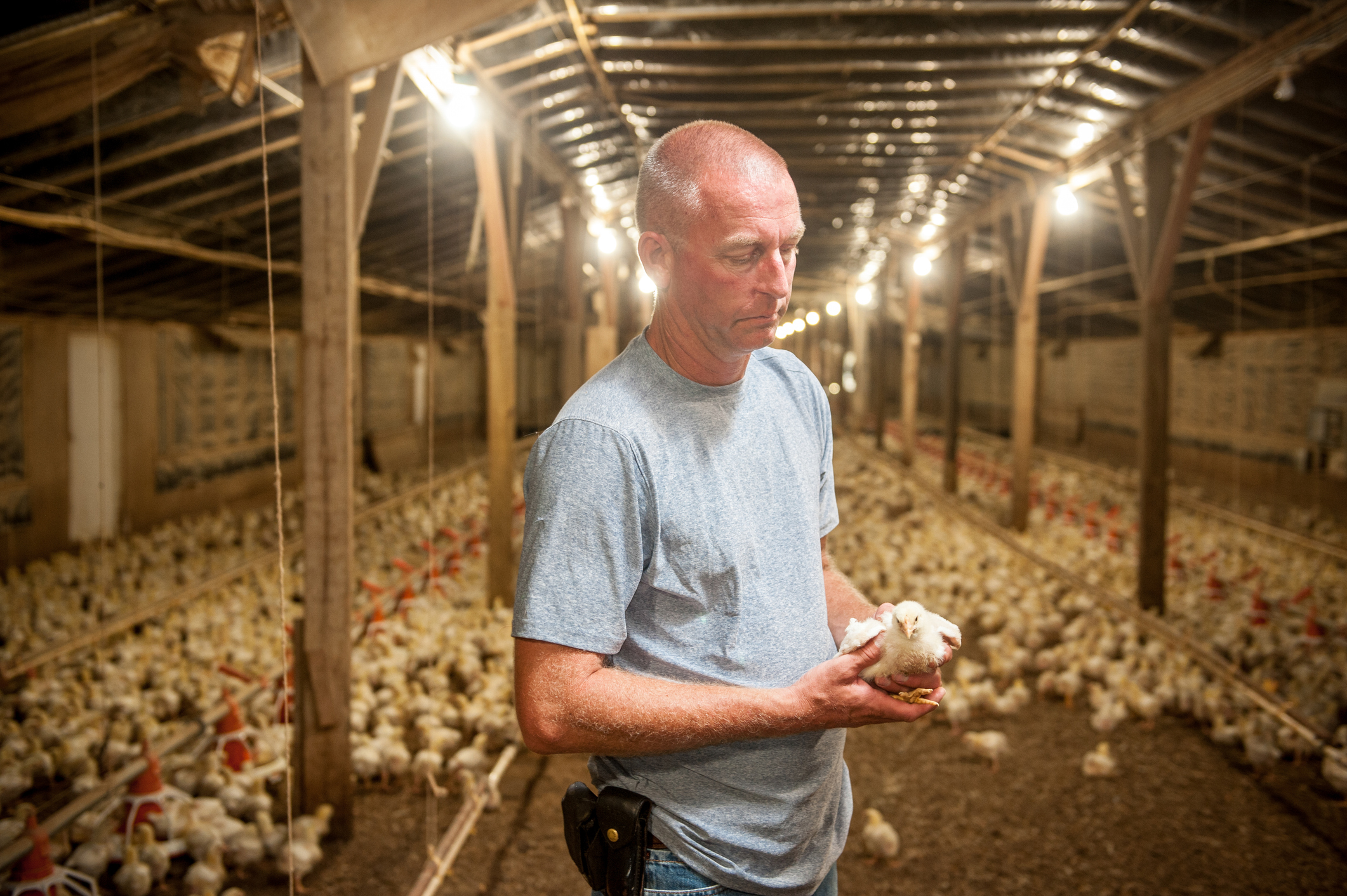

Since April 2024, more than 70 human cases have been confirmed in the U.S., the majority among workers exposed to the waste and milk of infected poultry and cows. Human H5N1 infections in the U.S. have ranged from relatively mild illness to severe pneumonia, depending on the degree of exposure: eye infections have resulted from being splashed with infected milk at dairy operations; severe infections are more likely to be associated with contact with sick and dying chickens.

The first human fatality in the U.S. was recorded in January 2025 in an individual exposed to wild birds and a backyard poultry flock.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) continue to assure the public that H5N1 currently poses very low risk to humans. But numerous epidemiologists, virologists, and biosecurity experts have expressed fears that with the right mutations or reassortment, the virus could develop the ability to spread between people.

“If that happens, it could ignite a pandemic” says Denis Nash, executive director of the CUNY Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health (ISPH) and distinguished professor of epidemiology. “So, the risk to humans is low – until it isn’t.”

The most likely way H5N1 could acquire the ability for sustained human-to-human transmission is through a process called reassortment, wherein two viruses present in the same host (a co-infection) exchange genetic material, producing a new virus with enhanced attributes. Reassortment can occur when a person (or animal) is infected with both H5N1 and the seasonal influenza that’s currently circulating in people. The result could be the creation of a flu virus that is both more pathogenic and capable of human-to-human transmission.

“Limiting opportunities for viral reassortment is a priority,” says Nash. “We need to prevent co-infection with seasonal flu and H5N1, and to do that, we have to control the spread of both viruses in people and in livestock.”

To prevent co-infection and potential reassortment, Nash says that our efforts should concentrate on the groups most at risk for H5N1 exposure: poultry and dairy workers. The government should promote the seasonal flu vaccine, consider providing those at high risk of H5N1 exposure access to the avian influenza vaccine, track the virus in livestock, and provide effective antiviral medications to anyone exposed to or infected with H5N1.

“As a salient example, seasonal flu is hitting NYC residents quite hard at the moment,” Nash notes. “And just recently, the first H5N1 outbreak in NYC was reported in a live bird market. How many of people working and visiting this market also had seasonal influenza? The chances of co-infection and reassortment are much higher during flu season, and having people vaccinated against flu, especially poultry and dairy workers, is a pragmatic strategy that can reduce the occurrence of seasonal flu infection, as well as its severity and duration among those most likely to be exposed to H5N1.”

The federal government has taken some steps to promote the seasonal flu vaccine among vulnerable workers and recommended that antiviral medications be offered to workers exposed to H5N1 as post-exposure prophylaxis. However, at this point, these recommendations represent an unfunded mandate for poultry and dairy farms, and data on their uptake and implementation has not been made available.

Vaccinating people against the H5N1 virus would be effective at reducing opportunities for co-infection and reassortment. The U.S. has a stockpile of H5N1 vaccine, but there has been no official move to distribute it, even to vulnerable workers. Notably, some European countries are already offering the H5N1 vaccine to workers on farms where bird flu has been detected.

Work is underway in the U.S. to develop H5N1 vaccines for livestock. Even this positive development is a cause for concern for some in the industry: their ability to export their products could be hindered because many countries won’t accept products from animals that have received vaccinations.

As far as tracking the virus as it spreads among dairy herds, the U.S. has been slow to implement comprehensive testing and reluctant to share data about the results of the testing it has done.

In an opinion piece in The Hill, CUNY SPH faculty Rachael Piltch-Loeb, Scott Ratzan and Nash assert that, “…we must systematically monitor the spread among cattle and other farm animals whether or not they show signs of illness. Local, state and federal government entities must then communicate this information with timeliness, intent and transparency. Effective communication can build trust before people are expected to take action.”

Tracking and testing too few dairy herds and workers

The U.S. government failed to eliminate the virus on dairy farms by moving quickly to identify infected cows and taking measures to keep their infections from spreading early on, when it was confined to a handful of states. Current actions to track and contain the virus are hardly encouraging.

While the USDA claims to be working “swiftly and diligently” to assess the prevalence of the virus in U.S. dairy herds and respond accordingly, the scale of their efforts has not been commensurate with the rapid spread of the virus.

In May of 2024, the USDA instituted a voluntary herd monitoring program that offers weekly bulk testing of milk for H5N1. However, of the roughly 24,000 dairy herds in the U.S., only 85 had enrolled in the program by January 2025.

The challenges are substantial: the dairy industry remains unconvinced of the benefits of surveillance and is reluctant to invite federal scientists to monitor their operations and test their livestock, fearing financial losses that federal compensation may not fully offset.

Meanwhile, dairy workers– the group most at risk–are often migrants who are reluctant to participate in testing due to fears that a positive test result could lead to job loss and potentially deportation.

In December 2024, the USDA issued a federal order for a national milk testing strategy to address H5N1. For a moment it seemed like the federal government was finally taking the massive step of conducting bulk milk testing on a national scale and not relying on dairy farms to volunteer. But the order, which requires individual dairy farms to share raw milk samples only upon official request, lacks teeth.

Conflicting missions

“The USDA’s responsibility is to support the economic livelihood of the agriculture industry, as well as regulate health and safety practices,” says Piltch-Loeb, assistant professor at CUNY SPH, an investigator at the ISPH, and Workforce Capacity and Preparedness Lead at the NYC Preparedness & Recovery Institute (NYC PRI). “Sometimes, those missions can be in opposition.”

Cracking down on the dairy and poultry industries to conduct and report comprehensive testing of their livestock and workers would likely be highly disruptive to their profitable operation, and the USDA appears reluctant to do that.

“The U.S. government subsidizes the dairy industry to the tune of $20 billion a year,” says Piltch-Loeb. “It would need to plow something like another $20 billion into compliance efforts to scale up testing to a meaningful level. It would be a massive undertaking, and at this point it doesn’t seem likely.”

Thus far the USDA has not been forthcoming about bulk milk testing requests they have made, nor the results from those tests. Slow-walking both virus tracking efforts and data sharing may be the order of the day.

“The incentive to identify and track an emerging pathogen at an early phase is firmly not there,” says Piltch-Loeb. “That is incredibly difficult to reconcile with something that could lead to a human health pandemic.”

Communication is key

Given the conflicts of interest and trickle of data, it’s hard to know who we should be listening to. As we saw with COVID-19, confusing and conflicting information breeds mistrust, and the absence of consistent communication leaves a vacuum that can quickly be filled with misinformation.

In a STAT op-ed, CUNY SPH Distinguished Lecturer Scott Ratzan and Senior Scholar Ken Rabin argued that government agencies need to declare when they will communicate about H5N1 and when they will not, and stick to the plan. Given the uncertainty surrounding the virus, they recommend that agencies develop a comprehensive intergovernmental communication plan based on multiple scenarios, and coordinate communication across agencies on a daily basis, with an emphasis on providing accurate and trustworthy information to the public.

“Communication is not an afterthought,” says Ratzan, who has spent three decades in health communication, health literacy, and strategic diplomacy. “It is absolutely central to emergency response and can be a deciding factor in maintaining control over the effects of an outbreak.”

CUNY SPH scientists are focused on aiding surveillance and protecting at-risk workers

Piltch-Loeb, whose background is in public health emergency preparedness and response, is working with the ISPH and the NYC PRI on preparedness research, evaluation, and practice.

“With H5N1 we have an opportunity to start educating people early, before the situation becomes dire,” she says. “Unlike the COVID-19 scenario where the pandemic was unfolding rapidly and we didn’t have all the answers, this time we have a better understanding of H5N1 epidemiology at an earlier point. Because of that, we can make public health recommendations at an earlier point in time that are based in scientific reality. But we have to recognize, people are tired of public health interventions that require changing day-to-day life. At this moment I think we are vastly unprepared for the population reaction if they are asked to take protective measures because of bird flu.”

“We’re working on ways to bring the relevant stakeholders to the table, folks like agricultural workers, dairy workers and food handlers,” says Piltch-Loeb. “Most dairy workers are Spanish-speaking migrants. They’re in direct contact with infected animals and raw milk, yet they lack the protections of occupational safety laws and have minimal access to health care.”

“Our goal is to identify opportunities for workforce training to help at-risk groups minimize their exposure to H5N1,” she continues. “We’re engaging colleagues who focus on occupational health to think through what those will look like, and we’re also working on convening different health practice groups to determine how vital information could reach the public in a timely manner.”

Wastewater surveillance

During the COVID-19 pandemic, wastewater testing demonstrated great potential for early detection of that threat on a large scale, providing hospitals and policy makers with advance warning of surges in their area well before the first cases were clinically identified. Wastewater surveillance systems are in place throughout the U.S.; most are part of the National Wastewater Surveillance System, which is supported by the CDC.

While this surveillance system is critical for national pandemic preparedness and response, scientists at the ISPH deemed the current system “vastly under-leveraged for H5N1 at this precarious moment” in a STAT opinion.

Wastewater surveillance for H5N1 is hindered by several challenges. Community based wastewater contains waste from both humans and animals, making it impossible to rapidly detect and differentiate human outbreaks of H5N1 from animal outbreaks.

In addition, current monitoring methods can only broadly detect influenza A viruses. This means that the avian influenza A (H5N1) virus can be detected but not distinguished from seasonal influenza A virus subtypes that have been circulating for years.

To address these limitations, the ISPH, in collaboration with teams at CUNY’s Queens College and NYC Health and Hospitals (H+H), to monitor wastewater at four H+H facilities. The Queens College team, led by Professor John Dennehy, previously established a similar surveillance program to detect SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Since H+H sites process human waste only, samples are free from contamination by livestock or wild animal runoff. The team also worked to validate and deploy genetic tests based on specific H5N1 sequences released by the USDA, for use in testing hospital wastewater in New York City.

“Given that influenza A subtypes are commonly circulating in the population, particularly during flu season, it will be crucial to develop more precise testing methods to detect the presence of H5N1 and any recombined version of the H5N1 outbreak strain with seasonal influenza viruses among humans,” says Nash.

Tracking severe respiratory infections across the U.S.

Nash recently told that a good bird flu preparedness plan would include the following: quick, scalable access to testing and masks, effective and widespread public health messaging, and swift vaccine production.

“We’re hopefully not going to be in a place like we were with COVID, where we couldn’t tell the extent of the outbreak, and how fast and where it was spreading until it was way too late,” he said. “If that happens with something like this virus, if it’s more pathogenic than COVID, we’ll be in a really bad place.”

Nash and his team at the ISPH, in collaboration with Pfizer, are focusing on severe respiratory infections currently circulating among the population. They recently launched a new prospective cohort study (n=6,000) of severe respiratory infections, called Project PROTECTS, which will be tracking influenza A, influenza B, RSV, and COVID-19 across the U.S. The project utilizes both at-home rapid antigen and PCR tests to investigate the incidence and symptom severity of these viruses. It also aims to address gaps in our understanding of the short- and long-term effects of these viruses on daily life, in the context of existing vaccines, background immunity, and treatments.

“If bird flu does eventually go off the rails, and starts spreading between people, this cohort could be fundamentally helpful in providing early insights around its spread and population health impact.” says Nash.

The last pandemic originated in Wuhan, China. If H5N1 becomes a pandemic, the origin will be the U.S.